Tudor Portraiture: Holbein, Power, and the Art of the Image

The Tudor era (1485–1603) was a period defined by seismic political and religious shifts, yet it was also an age where visual propaganda became an essential tool of governance. Before the widespread use of photography or mass media, the painted portrait served as the primary means by which monarchs projected their power, secured diplomatic alliances, and cemented their legitimacy. From the subtle symbolism of Henry VII to the dazzling, almost theatrical majesty of Elizabeth I, Tudor portraiture is far more than mere decoration; it is a vital historical document, a carefully curated narrative, and an enduring testament to the genius of artists like Hans Holbein the Younger.

Hans Holbein the Younger: The Master of Tudor Propaganda

No discussion of Tudor art can begin without acknowledging the towering influence of Hans Holbein the Younger (c. 1497–1543). Arriving in England initially seeking patronage from Sir Thomas More, Holbein soon became the court painter to Henry VIII, transforming the way the English monarchy was visually represented. Holbein’s style was revolutionary: meticulous realism combined with profound psychological insight and a mastery of symbolic detail. He didn't just paint faces; he painted status, wealth, and authority.

The Iconography of Henry VIII

Holbein’s most famous contribution was the definitive image of Henry VIII. The original mural, painted for the Privy Chamber at Whitehall Palace (destroyed by fire in 1698), established the King as an almost superhuman figure. Holbein depicted Henry in a confrontational, wide stance, clad in rich silks and furs, radiating confidence and overwhelming physical presence. This image was so successful that it became the template for all subsequent royal portraits, ensuring that even centuries later, we visualize Henry VIII through Holbein’s lens.

“The King stood there, so majestic and so terrible, that the beholder felt abashed and confounded.” – Karel van Mander, describing the impact of Holbein’s Whitehall mural.

Holbein’s efficiency was key to his success. He often used preparatory chalk drawings, known as 'cartoons' or 'patterns,' to capture the sitter's likeness quickly. These drawings allowed him to complete the final oil paintings with speed and accuracy, essential for a busy court needing portraits for diplomatic exchange and marriage negotiations.

Did You Know?

Holbein’s portrait of Anne of Cleves was crucial in securing her marriage to Henry VIII. However, when Henry met her in person, he famously complained that the portrait flattered her, leading to the swift annulment of the marriage. This incident highlights the immense political stakes involved in Tudor portraiture.

Beyond Holbein: The Rise of Native and Continental Artists

While Holbein set the standard, the demand for portraits throughout the 16th century surged, fueled by the rising gentry and nobility who sought to emulate royal fashion. After Holbein's death in 1543, the court relied on a succession of talented artists, both English and foreign, who adapted and evolved the Tudor style.

- William Scrots: Active during the reigns of Henry VIII and Edward VI, Scrots introduced elements of Mannerism, characterized by elongated forms and sophisticated, sometimes unsettling, compositions. His portrait of Edward VI shows a move towards greater formality.

- Hans Eworth: A Flemish artist who dominated the mid-Tudor period, Eworth specialized in rich, detailed portraits often featuring complex allegorical elements, particularly during the reign of Mary I.

- The Limners: Smaller, miniature portraits became incredibly popular, often carried in lockets or worn close to the heart. Nicholas Hilliard and Isaac Oliver were the masters of this intimate art form, capturing incredible detail on vellum or card.

Nicholas Hilliard and the Elizabethan Image

The reign of Elizabeth I marked the zenith of Tudor portraiture. Elizabeth understood the power of her image better than any monarch before her. She carefully controlled how she was depicted, ensuring that her portraits conveyed stability, divinity, and eternal youth, even as she aged.

Nicholas Hilliard (c. 1547–1619), the Queen’s principal limner, was instrumental in crafting this iconic image. His miniatures and larger panel portraits are characterized by their delicate, almost fairy-tale quality, emphasizing the Queen’s pale complexion, elaborate ruffs, and shimmering jewels.

Hilliard famously captured the Queen's preference for light and lack of shadow, believing shadows obscured the true likeness. This preference reinforced the idea of the Queen as a divine, almost ethereal being.

Symbolism and Subtlety in Tudor Painting

Tudor portraits were rarely straightforward representations; they were dense with symbolic meaning, requiring the educated viewer to 'read' the painting. Every element—from the choice of background to the specific items held by the sitter—was deliberate.

Decoding the Details

- Jewels and Clothing: Indicated wealth and status. The sheer volume of pearls often symbolized purity, particularly in Elizabeth I’s portraits.

- Gloves: A sign of refinement, often used in diplomatic gifts.

- Books and Instruments: Suggested learning, piety, or specific intellectual pursuits (e.g., a compass for navigation or mathematics).

- Animals and Plants: Specific flora and fauna carried moral or political weight. Roses (Tudor emblem), carnations (betrothal), or ermine (royalty and purity) were common motifs.

- The Sieve (Sieve Portrait): Used in portraits of Elizabeth I, referencing the Roman Vestal Virgin Tuccia, symbolizing the Queen's virginity and incorruptibility.

The famous 'Ditchley Portrait' of Elizabeth I (c. 1592) is perhaps the ultimate example of symbolic portraiture. The Queen stands atop a map of England, literally dominating her realm, while storm clouds recede and the sun breaks through, signifying peace and prosperity under her rule.

The Legacy of the Tudor Image

The influence of Tudor portraiture extended far beyond the 16th century. The techniques pioneered by Holbein—the use of preparatory drawings, the emphasis on status through clothing, and the controlled dissemination of the royal image—established conventions that lasted for centuries in European court painting.

Furthermore, the demand for these images created an industry. Workshops produced numerous copies of royal portraits, often of varying quality, to satisfy the public's desire for a connection to the monarch. This proliferation ensured that the carefully constructed Tudor narrative reached every corner of the kingdom, reinforcing loyalty and obedience.

“The portrait of a prince is a public thing, and should be made to serve the state.” – A contemporary observation reflecting the political utility of royal images.

Studying these portraits today offers historians invaluable insight into the material culture, fashion, and political ideology of the time. They reveal the anxieties, aspirations, and meticulously managed public faces of one of England’s most dramatic dynasties. From the severe, powerful gaze of Henry VIII to the dazzling, semi-mythical representation of the Virgin Queen, Tudor portraiture remains a captivating window into a world where art and power were inextricably linked.

To truly understand the Tudor age, we must not only read the documents but also learn to read the paintings, appreciating the sophisticated artistry and deliberate political messaging hidden beneath the velvet and gold. The brushstrokes of Holbein, Hilliard, and their contemporaries continue to shape our understanding of England's most famous royal house.

TAGS

Discussion

No comments yet

Be the first to share your thoughts on this article!

Related Articles

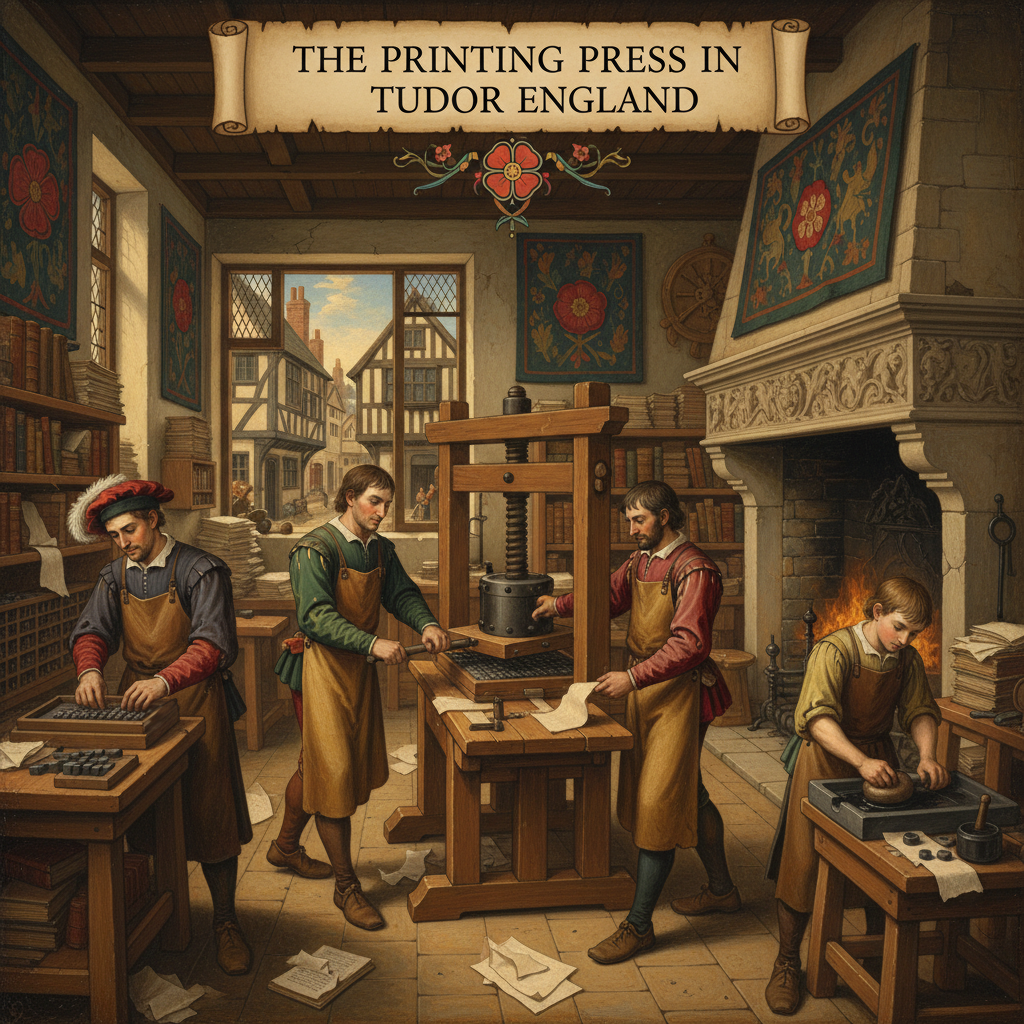

Ink, Ideas, and Revolution: The Printing Press in Tudor England

Explore the revolutionary impact of the printing press in Tudor England, from its arrival with William Caxton to its pivotal role in the Reformation and the Crown's attempts at censorship.

Shakespeare's Tudor World: Drama, Power, and Politics

Explore how William Shakespeare’s life and works were profoundly shaped by the political volatility, religious upheaval, and cultural vibrancy of the Tudor era under Queen Elizabeth I.