Shakespeare's Tudor World: Drama, Power, and Politics

William Shakespeare, the greatest playwright in the English language, was not merely a chronicler of history; he was a product of his time—the vibrant, volatile, and intellectually explosive Tudor era. Born in 1564, just six years into the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, Shakespeare’s formative years and the peak of his career coincided perfectly with the golden age of Tudor England. To understand Shakespeare’s genius, one must first understand the world that shaped him: a world defined by religious upheaval, burgeoning nationalism, fierce political intrigue, and a profound fascination with classical history and the nature of kingship. His plays are not just timeless dramas; they are mirrors reflecting the anxieties, ambitions, and daily life of late Tudor society.

The Elizabethan Stage: A Crucible of Tudor Culture

The rise of professional theatre was intrinsically linked to the stability and prosperity of Elizabeth I’s reign. Before the 1570s, acting troupes were often viewed with suspicion, regarded as vagabonds unless patronized by nobility. Elizabeth’s government, however, recognized the potential for both propaganda and public control inherent in the theatre. The establishment of permanent playhouses, such as The Theatre (1576) and later the Globe (1599), transformed London’s Bankside into a bustling cultural hub.

Patronage and Censorship: Walking the Political Tightrope

Shakespeare’s company, initially known as the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, enjoyed high-level patronage, which was crucial for survival. This connection provided protection but also subjected the company to strict governmental oversight. The Master of the Revels held the power of censorship, ensuring that nothing treasonous, religiously controversial, or overtly critical of the Queen or her policies made it to the stage.

This political environment forced Shakespeare to be incredibly subtle. He often used historical settings—particularly Roman and earlier English history—as allegorical vehicles to discuss contemporary issues. For instance, plays dealing with deposition and rebellion, like Richard II, were highly sensitive. The Essex Rebellion in 1601 famously involved the rebels commissioning a performance of Richard II on the eve of their uprising, hoping to inspire public support for the deposition of the Queen, highlighting the real political power of Shakespeare’s work.

“The Queen’s Majesty hath been greatly offended with the playing of Richard II, and especially with the deposition scene.” – William Lambarde, Keeper of the Records in the Tower of London, 1601 (referencing Elizabeth I’s reaction).

Kingship, Succession, and the Tudor Myth

A central theme running through Shakespeare’s history plays is the concept of legitimate rule and the devastating consequences of civil war. This was not an abstract academic exercise; it was the foundational political doctrine of the Tudor dynasty.

Forging the Tudor Identity

The Tudors, descended from Henry VII, who seized the throne at the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485, were acutely aware of the fragility of their claim. They actively promoted the ‘Tudor Myth,’ a narrative that painted the preceding Wars of the Roses as a period of divine punishment for the deposition of Richard II, culminating in the glorious, God-ordained salvation brought by the Tudors.

- Henry VI Trilogy: Depicts the chaos and breakdown of order when weak kings rule.

- Richard III: Portrays the last Plantagenet king as a monstrous tyrant, justifying Henry VII’s conquest.

- Henry V: Celebrates the ideal English warrior king, embodying national unity and strength—a clear parallel to Elizabeth I’s own image.

Shakespeare’s histories, therefore, served a dual purpose: they were thrilling dramas and powerful endorsements of the established political order. They reinforced the idea that political stability depended entirely on the monarch’s legitimacy and strength, a message vital during the uncertainties of Elizabeth’s childless reign.

Did You Know?

Shakespeare's history plays, particularly the Henriad (Richard II, Henry IV Parts 1 & 2, Henry V), were instrumental in standardizing the English perception of these historical figures, often overshadowing actual historical records. His version of Richard III, for example, remains the dominant cultural image, despite significant historical debate about his true character.

Religion, Superstition, and the Human Condition

The Tudor era was defined by the English Reformation, a seismic shift that fundamentally altered England’s religious and political landscape. While overt religious commentary was strictly forbidden on the stage, the spiritual anxieties of the age permeate Shakespeare’s tragedies.

The Ghostly Presence of Catholicism

By the time Shakespeare was writing, England was officially Protestant. Yet, many older traditions and superstitions lingered. The appearance of ghosts in plays like Hamlet and Macbeth holds deep significance in a post-Reformation world. The ghost of Hamlet’s father, who is described as being in Purgatory, is a decidedly Catholic concept. In Protestant theology, Purgatory did not exist, suggesting that Shakespeare was tapping into older, perhaps dangerous, spiritual traditions still held by many of his audience members.

Furthermore, the tension between fate and free will—a core theological debate of the time—is explored relentlessly. Characters like Macbeth struggle with predestination (the witches’ prophecies) versus their own moral choices, reflecting the complex theological environment of the late Tudor and early Stuart periods.

The Language of the Court and the Street

Shakespeare’s mastery of language reflects the linguistic dynamism of the Tudor age. The influx of new words from exploration, classical learning (fueled by the Renaissance), and the standardization of English following the introduction of the printing press provided him with an unprecedented palette. His vocabulary, estimated at over 20,000 words, showcases the intellectual vigor of Elizabethan England. His plays were performed not just for the Queen and the nobility, but for the 'groundlings'—the common people standing in the yard—requiring a language that could simultaneously soar with poetic elegance and connect with bawdy, earthy humor.

The Transition to the Stuarts: A New Reign, A New Focus

Queen Elizabeth I died in 1603, marking the end of the Tudor dynasty and the accession of James I (James VI of Scotland), the first Stuart king. This transition profoundly affected Shakespeare’s career.

Immediately upon James’s accession, Shakespeare’s company was elevated to the King’s Men, a testament to their prestige and the new monarch’s appreciation for the arts. James I, a scholar and a patron of the arts, brought his own political interests to the fore, particularly his fascination with witchcraft, kingship, and Scottish history.

Shakespeare responded directly to this new political climate. Macbeth (c. 1606), with its focus on regicide, the supernatural, and its setting in Scotland, is widely seen as a direct tribute to the new king. Similarly, King Lear (c. 1606) explores themes of dividing kingdoms and the breakdown of paternal authority, topics highly relevant to James I’s vision of a unified Great Britain.

The Tudor era provided the foundation—the history, the political anxiety, and the theatrical infrastructure—but the Stuart era allowed Shakespeare to delve into darker, more complex psychological territories, building upon the dramatic traditions he perfected under Elizabeth.

Shakespeare’s Enduring Tudor Legacy

William Shakespeare’s career spanned the most glorious period of the Tudor age and its immediate aftermath. His works are invaluable historical documents, offering historians a window not just into the grand narratives of kings and queens, but into the social customs, legal practices, and philosophical debates of the late 16th century. From the bustling London streets filled with apprentices and merchants, to the courtly intrigue of Greenwich Palace, Shakespeare captured the essence of the Tudor spirit—ambitious, poetic, and deeply concerned with the nature of power.

To study Shakespeare is to study Tudor England. His tragedies remind us of the precariousness of power under Elizabeth, his comedies reflect the vibrant social life, and his histories solidify the political narrative that defined the dynasty. He remains the definitive voice of a golden age, ensuring that the echoes of Tudor glory continue to resonate on stages worldwide.

TAGS

Discussion

No comments yet

Be the first to share your thoughts on this article!

Related Articles

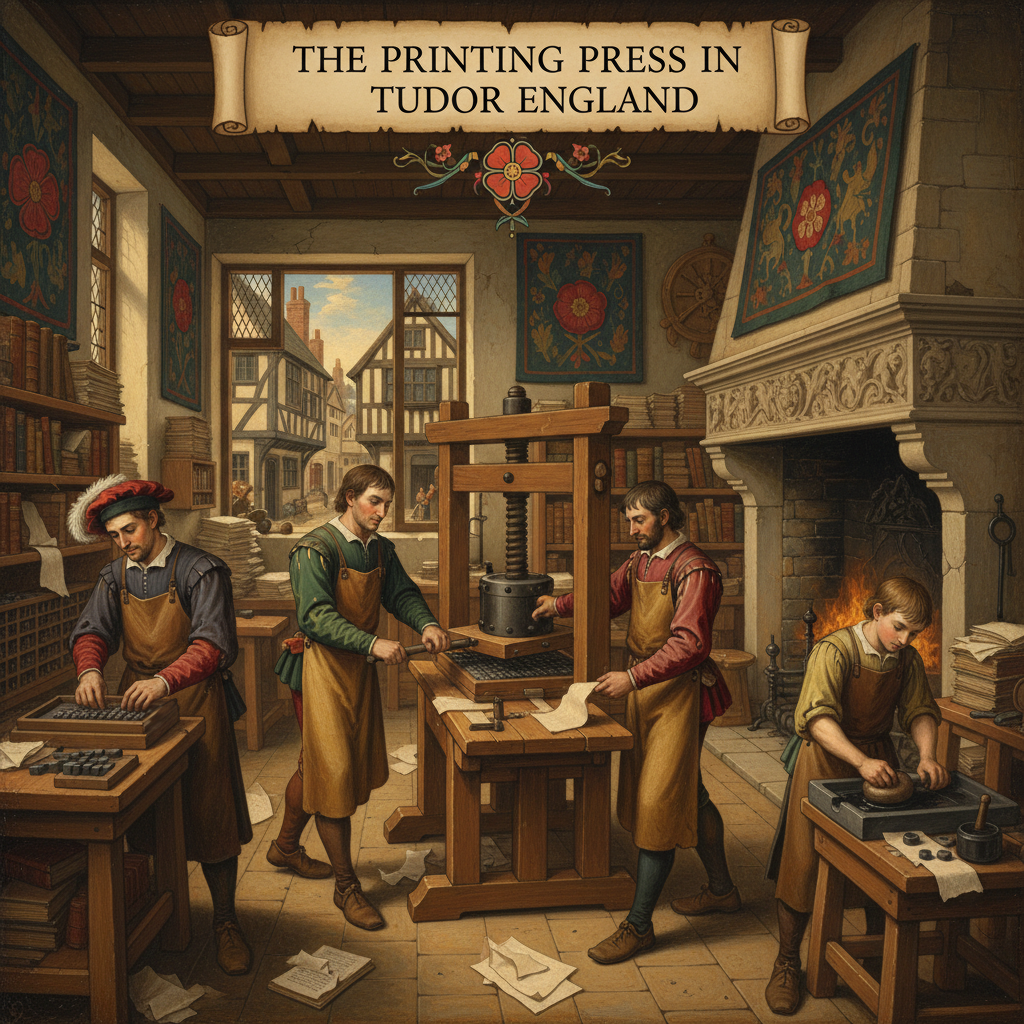

Ink, Ideas, and Revolution: The Printing Press in Tudor England

Explore the revolutionary impact of the printing press in Tudor England, from its arrival with William Caxton to its pivotal role in the Reformation and the Crown's attempts at censorship.

Tudor Portraiture: Holbein, Power, and the Art of the Image

Explore the revolutionary world of Tudor portraiture, examining how artists like Hans Holbein the Younger and Nicholas Hilliard shaped the public image of monarchs like Henry VIII and Elizabeth I, turning art into essential political propaganda.