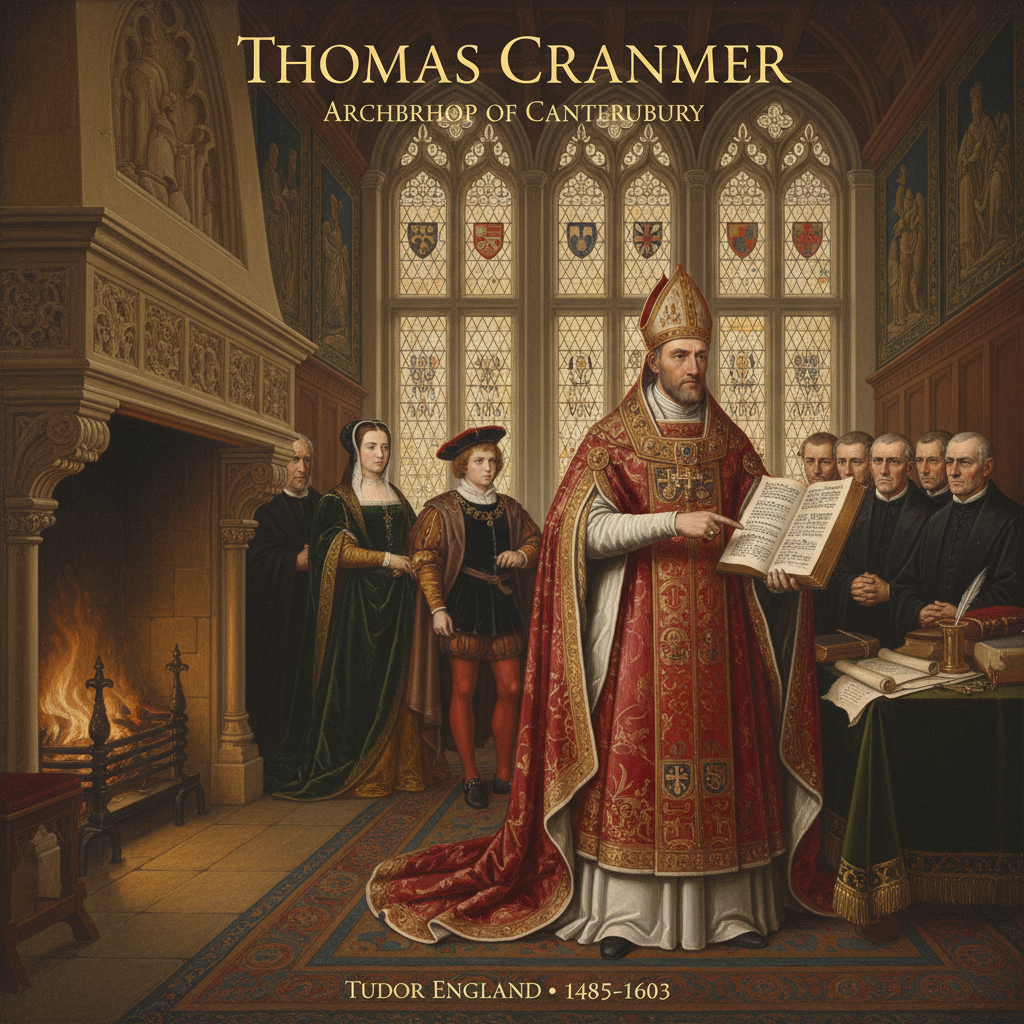

Thomas Cranmer: Architect of the English Reformation

In the tumultuous tapestry of Tudor England, few figures cast a shadow as long and complex as Thomas Cranmer, the first Protestant Archbishop of Canterbury. His name is inextricably linked with the seismic shifts of the English Reformation, a period when England broke from papal authority, reshaped its religious identity, and laid the foundations for the Church of England we know today. Far from a mere bystander, Cranmer was a principal architect, a scholar whose theological convictions, coupled with a pragmatic political acumen, guided King Henry VIII through the labyrinthine process of annulment and the subsequent establishment of a new ecclesiastical order. His journey, from humble origins to the highest spiritual office in the land, was fraught with peril, intellectual struggle, and ultimately, martyrdom, leaving an indelible mark on English history and faith.

The Scholar's Ascent: From Cambridge to Court

Born in Aslockton, Nottinghamshire, in 1489, Thomas Cranmer's early life gave little indication of the revolutionary path he would eventually tread. He was educated at Jesus College, Cambridge, where he immersed himself in theology, Latin, and Greek. Unlike many of his contemporaries who pursued careers in law or the church for advancement, Cranmer was a genuine scholar, deeply engaged with the burgeoning humanist movement and the reformist ideas emanating from continental Europe. His academic career was briefly interrupted by marriage, which, under the rules of the time, meant forfeiting his fellowship. However, the untimely death of his wife allowed him to regain his position and continue his studies, eventually leading to his ordination as a priest.

Cranmer's unexpected entry into the royal court was a stroke of serendipity. In 1529, while staying with relatives to avoid the sweating sickness, he encountered Stephen Gardiner and Edward Foxe, two of Henry VIII's chief advisors. During a discussion about the King's 'Great Matter' – his desire to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon – Cranmer proposed a novel solution: instead of endlessly petitioning the Pope, Henry should seek the opinions of universities across Europe, arguing that if they deemed the marriage unlawful, the King could then act on his own conscience. This ingenious suggestion immediately caught the King's attention. Henry, ever eager for a way to legitimize his divorce and secure a male heir, exclaimed, "I have found the man who has the sow by the right ear!"

Did You Know?

Cranmer's initial suggestion to Henry VIII about consulting universities was not entirely new, but his emphasis on the theological rather than purely legal aspects, and the implication of royal supremacy, resonated deeply with the King's own desires for absolute authority.

From that moment, Cranmer's trajectory was set. He was dispatched to Rome and then to Germany, where he engaged with leading Protestant reformers, including Andreas Osiander, whose niece, Margarete, he secretly married – a clear sign of his own evolving reformist sympathies, as clerical marriage was forbidden by the Catholic Church. His diplomatic missions, though not immediately resolving the annulment, cemented his reputation as a learned and trustworthy servant of the King.

Archbishop and Reformer: Shaping the Church of England

In 1532, upon the death of Archbishop William Warham, Henry VIII, against Cranmer's initial reluctance, appointed him Archbishop of Canterbury. Cranmer was consecrated in March 1533, and within months, he declared Henry's marriage to Catherine null and void, and his marriage to Anne Boleyn valid. This act, sanctioned by the highest ecclesiastical authority in England, effectively severed England's ties with Rome and paved the way for the Act of Supremacy in 1534, which declared Henry VIII the Supreme Head of the Church of England.

Cranmer's role, however, was far more than just a rubber stamp for Henry's marital affairs. He became the intellectual and spiritual leader of the English Reformation, carefully navigating the treacherous waters of royal politics and theological innovation. While Henry VIII was primarily interested in political control over the Church, Cranmer was driven by a profound desire for religious reform, seeking to cleanse the Church of what he saw as corruptions and superstitions and to bring it closer to what he believed was the true, evangelical faith.

"He was a man of such mild and gentle behaviour, that he was never heard to give any opprobrious speech, or to call any man by any ill name. He was a man of such a singular good nature, that he was never heard to speak ill of any man, no not of his greatest enemies."

– John Foxe, Actes and Monuments (Book of Martyrs)

Under Cranmer's guidance, significant changes were implemented:

- The English Bible: Cranmer was instrumental in promoting the translation and widespread distribution of the Bible in English, ensuring that ordinary people could read and understand scripture for themselves. The Great Bible, with Cranmer's preface, became a powerful symbol of the new religious order.

- Abolition of Superstition: He oversaw the dismantling of shrines, the removal of images, and the suppression of monasteries, redirecting their wealth to the Crown and their spiritual functions to parish churches.

- Liturgical Reform: Cranmer's most enduring legacy is arguably his work on the liturgy. During the reign of Henry's son, Edward VI, Cranmer produced the first and second Books of Common Prayer (1549 and 1552). These liturgical texts, written in eloquent English prose, replaced the Latin Mass and provided a standardized, accessible form of worship for the English people. They emphasized congregational participation, scripture reading, and a more Protestant understanding of the sacraments.

Cranmer's theological views evolved considerably throughout his life, moving from a position close to Lutheranism to a more distinctly Zwinglian or Reformed perspective, particularly concerning the Eucharist. This evolution is clearly visible in the revisions between the 1549 and 1552 Prayer Books, with the latter adopting a more symbolic interpretation of Christ's presence in communion.

The Perils of Faith: Under Edward VI and Mary I

With the accession of the devoutly Protestant Edward VI in 1547, Cranmer found himself in a position to implement his reforms more fully. The young king, guided by his Protestant regents, allowed Cranmer greater freedom to shape the religious landscape of England. It was during this period that the two Books of Common Prayer were published, along with the Forty-Two Articles of Religion (later reduced to the Thirty-Nine Articles), which laid out the doctrinal foundations of the Church of England.

However, the premature death of Edward VI in 1553 plunged England into a new religious crisis. Mary I, Henry VIII's staunchly Catholic daughter, ascended the throne, determined to reverse the Reformation and restore England to the Roman Catholic fold. Cranmer, along with other prominent Protestant leaders, was immediately arrested and charged with treason for his support of Lady Jane Grey's claim to the throne (an act he later recanted). His true crime, in Mary's eyes, was heresy.

Cranmer endured a lengthy and brutal imprisonment, subjected to intense pressure and theological debate. Under duress, and perhaps weakened by his ordeal, he signed several recantations, renouncing his Protestant beliefs and affirming Catholic doctrine. These recantations were a devastating blow to the Protestant cause and a propaganda victory for Mary's regime.

Martyrdom and Legacy

Despite his recantations, Mary I was determined to make an example of Cranmer. On March 21, 1556, he was brought to St. Mary's Church in Oxford, ostensibly to make a final public recantation before his execution. However, in a dramatic and defiant turn, Cranmer publicly renounced his recantations, declaring that his hand, which had signed the false documents, would be the first to burn.

"And as for the Pope, I refuse him, as Christ's enemy, and antichrist, with all his false doctrine. And as for the sacrament, I believe as I have taught in my book against the Bishop of Winchester, the which my book teacheth so true a doctrine of the sacrament, that it shall stand at the last day before the judgment of God, where the papistical doctrine contrary to it shall be ashamed to show her face."

– Thomas Cranmer's final speech, as recorded by John Foxe

He was immediately dragged to the stake. True to his word, as the flames engulfed him, he held out his right hand into the fire, crying, "This unworthy right hand!" His courageous martyrdom, alongside those of Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley, became a powerful symbol for Protestants, immortalized in John Foxe's Book of Martyrs.

Thomas Cranmer's legacy is immense and multifaceted. He was a scholar, a diplomat, and a theologian who, through his intellect and perseverance, guided England through one of its most transformative periods. He laid the liturgical and doctrinal foundations of the Church of England, creating a distinctively English form of Protestantism that sought a middle way between Roman Catholicism and the more radical continental reforms. His Book of Common Prayer remains a masterpiece of English prose and a cornerstone of Anglican worship worldwide. Though his life ended in tragic circumstances, his unwavering commitment to his reformed faith in his final moments cemented his place not just as an architect of the English Reformation, but as one of its most revered martyrs. His story continues to remind us of the profound impact individuals can have on the course of history and the enduring power of conviction.

TAGS

Discussion

No comments yet

Be the first to share your thoughts on this article!

Related Articles

Catherine Howard: The Tragic 'Rose Without a Thorn'

Explore the tragic story of Catherine Howard, Henry VIII's fifth queen, the 'Rose Without a Thorn,' whose youthful exuberance and hidden past led to her dramatic downfall and execution.

The Howard Family: Power, Peril, and Dukes of Norfolk

Explore the dramatic saga of the Howard family, Dukes of Norfolk, from their rise to power and influence in Tudor England to their perilous proximity to the crown and their enduring legacy.